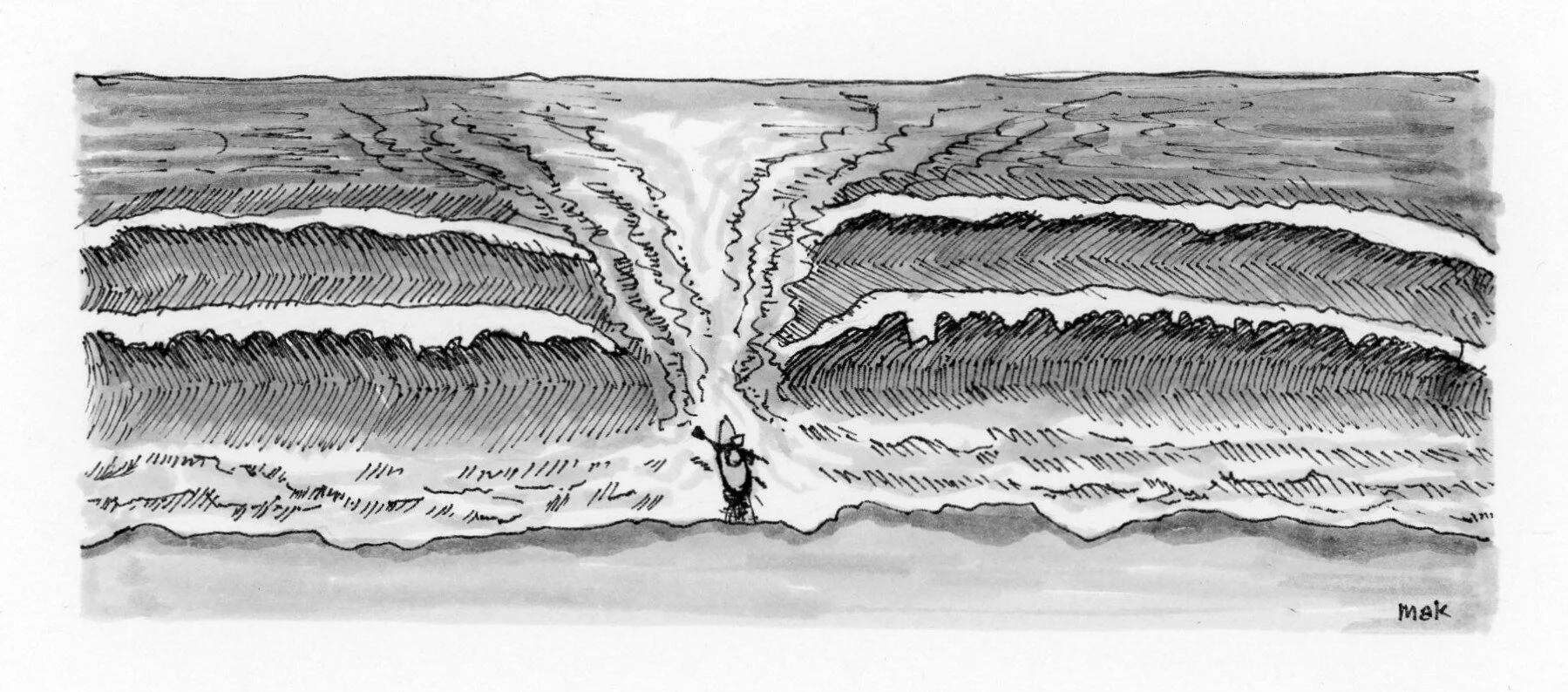

Dynamic Water: What Watercolor Teaches Me about Sea Kayaking

Art and words by Mary Ann King

I love sea kayaking and watercolor because they tap into extreme beauty, they are so fun, they give me avenues and freedom to explore nature, and they push me out of my comfort zone. Over the last few years, as I’ve made an effort to get better at both, I’ve started to notice some uncanny parallels: feedback from my watercolor class would unlock a kayaking skill, or something would click in my painting after I spent time out the Gate. So, I offer a few humble observations with the hope that something I’ve gleaned from watercolor painting resonates with your own kayaking (or other) journey.

Dynamic water. One of the things that distinguishes watercolor from the other media I like is that the water is dynamic. This fluid movement of color — working with what the water is going to do, and where and how it’s going to flow, and being creative with more (or less) water than I anticipated — is what makes it so beautiful and so challenging. The watercolor skills I’m working on sound a lot like kayaking skills:

-

Practicing and building an understanding of different techniques and when and how to apply them (depending on what I am trying to do and the circumstances I find myself in).

-

“Being mindful of [my] edges. Tend to them.” That’s a quote from my watercolor teacher, but very well could have been from any kayak class. Edge awareness is one way to work with rather than against your water and your paint.

-

Exploring different paints, different mixtures of paints, different brush types and sizes, and varying amounts of pressure. Being open to and observing the (seemingly infinite) combinations that result.

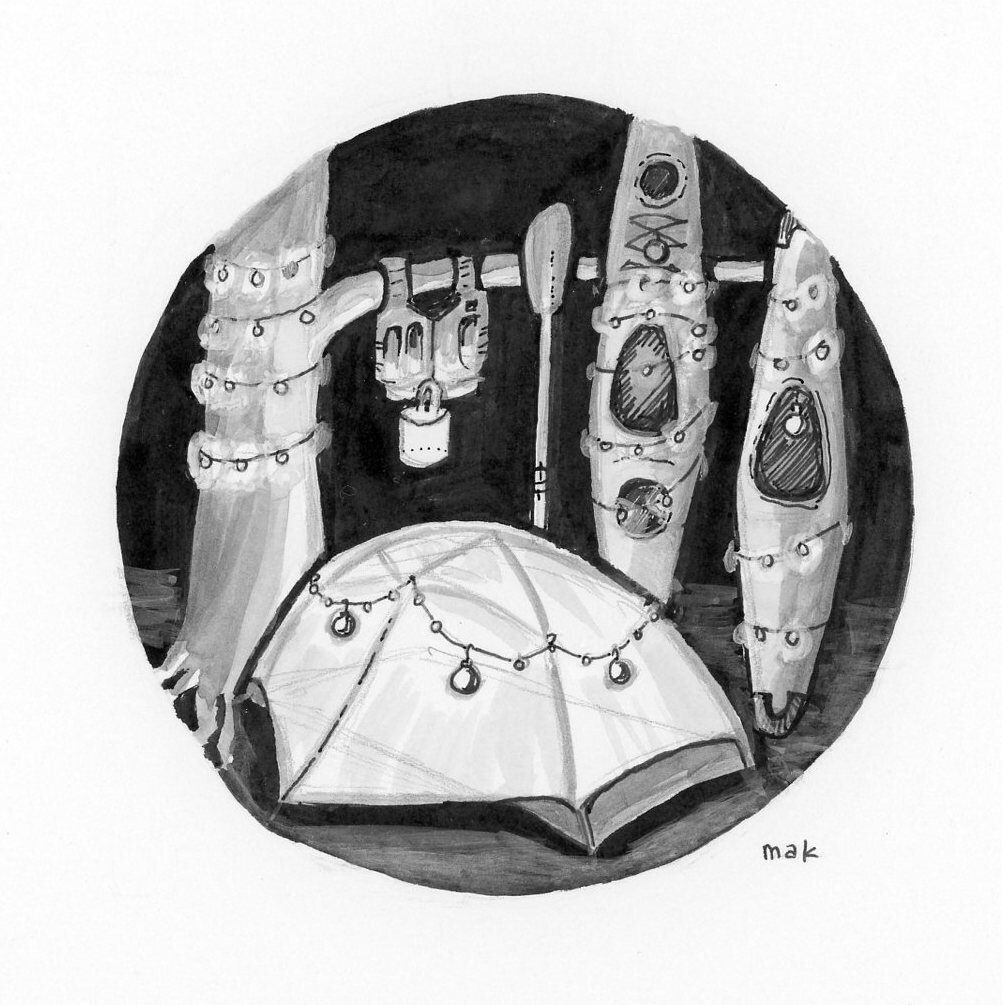

PLaY! Try it. Doodle. Recently, I was having trouble with an area of a painting and asked my teacher for advice on getting unstuck. His suggestion: “Try reframing it as a test, as play. What is going to happen if you make a big mess? No watercolor police are going to come and take away your brushes. You don’t have to show anyone. All that happens is what happens, and then you have the experience, and you will be learning a lot of good stuff.” I’ve been watching how my kayaking instructors and friends create and hold space that enables people to try new things, push perceived limits, and experiment without the fear of making a mistake or feeling embarrassed. And I have been fortunate to experience first-hand how much play (and joy) seem to be at the heart of all of this.

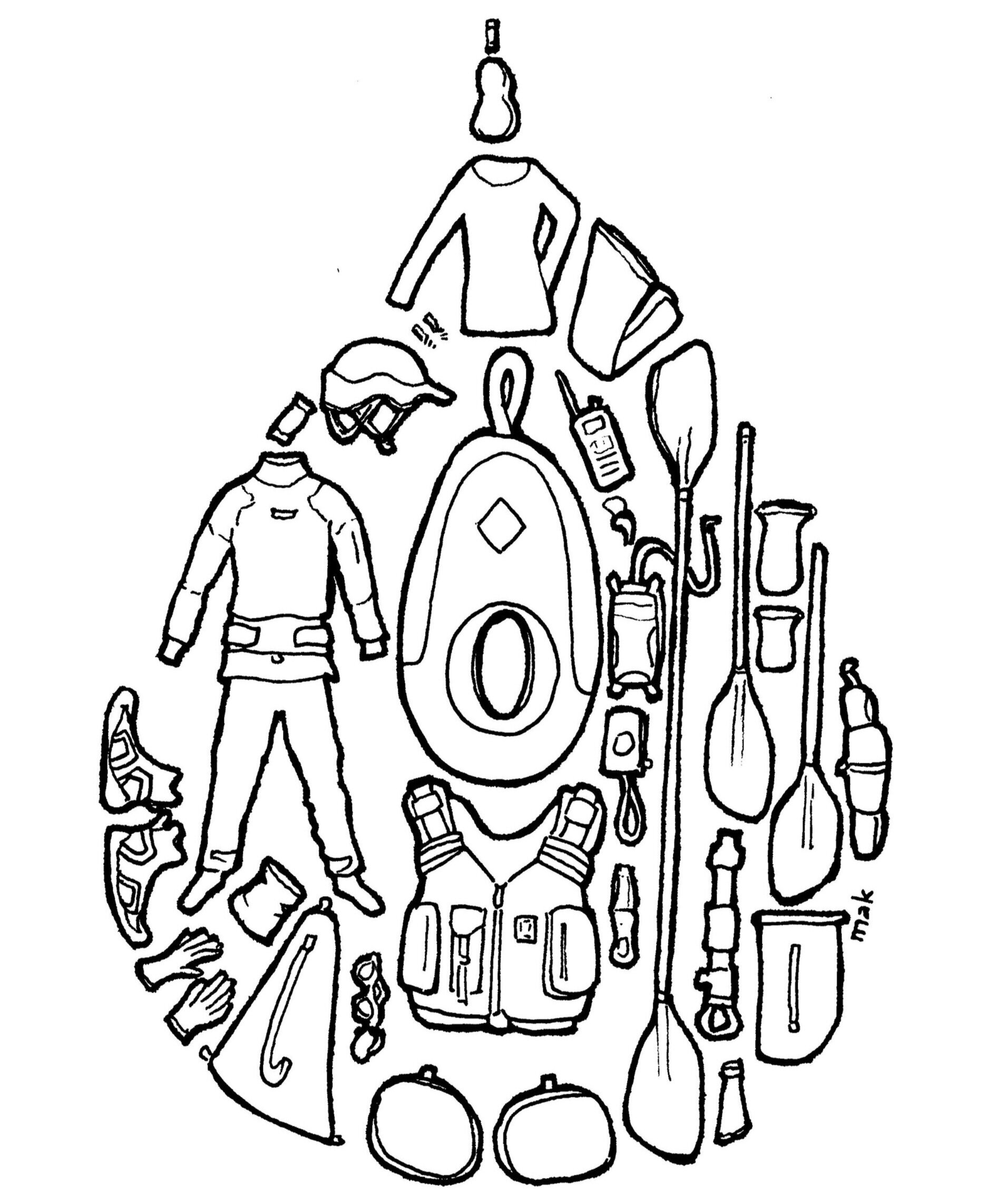

Establishing a practice. I think we have a tendency to attribute a “successful” project or polished technique to someone being a great artist, as if that were innate or fixed, and yet so much of art is building muscle memory and familiarity with your medium — and spending time observing. The teachers who have taught me the most quickly pivot to how many times they have done something, how much experimentation was involved, how non-linear their path is, and how much they practice. They’ve also taught me to pay close attention to how I organize my own practice. For example, do I start with the more general items (shapes, colors, lights and darks / um – body, boat, blade) and then elaborate on the details? Do I hone in on the details first and work on what I am already good at or accustomed to? Paying attention to why some things are easier or harder than others for me in practice has taught me a ton.

Disengaging our thinking (and judging) brain. Our brains filter how we observe things (check out this crazy article), and there is a mountain of fun art exercises that bypass the judgy part of the brain and engage the part that creates. They work by speeding things up (working faster so your muscles outpace your thinking), by changing where you focus (i.e., looking only at what you are drawing and not at your paper), by turning things upside down (forcing you to see and draw an object as a series of component parts — like shapes or lines — instead of what you think it should look like), and by using your non-dominant hand (building new muscle memory between your eyes and your hand). The equivalent of this in the kayaking realm has transformed my paddling. Things like: trying a skill with my eyes closed, looking where I am going instead of at my boat or blade, making it a competition, adding a ball (the best), getting out of my cockpit and on to my deck (out of the boat is the new in the boat), paddling with a swamped cockpit, and speeding up a drill so I am not thinking about what I am doing — I am purely doing.

Pointing positive in feedback. I’ve met way too many people in art classes who drew incessantly as kids…up until someone told them their art sucked. This got me reflecting on the extent to which how feedback is communicated (and received) shapes our journeys. I’ve been curious about how the people who inspire me (in art and kayaking) provide feedback to me, others, and (maybe most importantly) themselves. Here are some of my take-aways from watching them:

-

Pointing positive. Focusing more on what is working than not working, being even more emphatic about what works when it really works.

-

Celebrating when people make their own corrections and adjustments.

-

Reframing setbacks as normal and an important part of the process.

-

Lots of “we,” recognizing that many of the challenges we experience as a community of artists/kayakers trying to improve are common.

-

Having feedback originate not from ego, but rather from a place of competence, humility, perpetual and mutual learning, and a desire to elevate others.

-

Knowing when to be direct. I’m grateful to have people I trust call out when I’ve fallen back into an old pattern or when I’m capable of challenging myself more.

Getting yourself comfortable. Again, to quote a watercolor teacher: “If you need to make a long mark or an important brush stroke, get yourself and your paper in a position where you are comfortable.” This has so many layers, from making sure I am comfortable in my boat; to paddling with people that I trust on a physical and emotional level; to remembering to breathe, relax, laugh, and smile when I undertake a challenge; and to harnessing those moments where I am comfortable and have support as opportunities to really push myself.

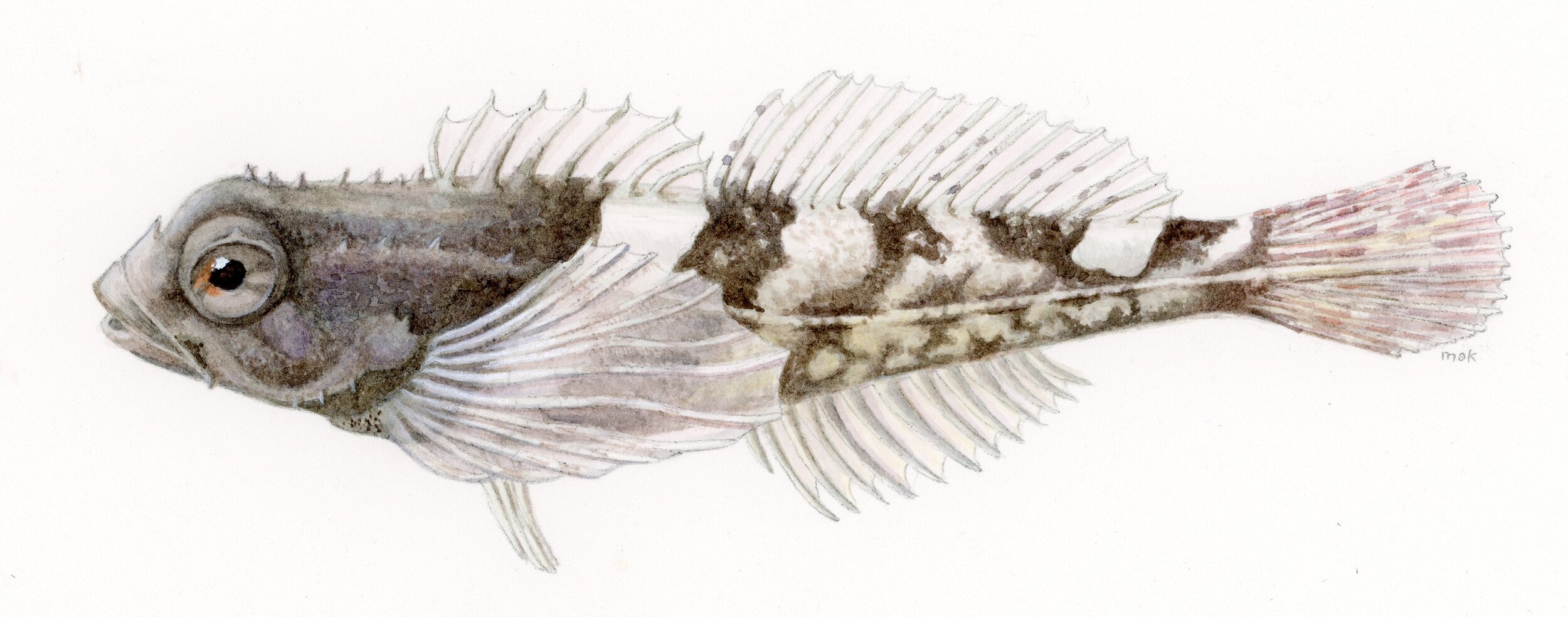

Salt is especially fun. Gonna end on salt. Go throw salt on your watercolor and paddle in the ocean and see what adventures unfold!

Thanks to Laura Zulliger, Pablo Villicaña Lara, Amadeo Bachar, Nigel Graham, Peter Hargreaves, Sheila Metcalf-Tobin, Jeff Atkins, Sally Fairfax and all the friends, teammates, teachers, instructors, and coaches who have taught me so much about art and kayaking (and learning and teaching).

About Saltwater Program Coach, Mary Ann King

Mary Ann exudes pure joy every time she’s on the water. She is a three-time US kayak polo national champion, and — before she fell in love with sea kayaking — represented the US on the Women’s National Kayak Polo Team at the World Games, Canoe Polo World Championships, and Pan American Kayak Polo Championships. Mary Ann is no stranger to hard work, performance kayaking, and disciplined coaching. She applies her keen sense of observation to provide students with feedback that leads to breakthroughs big and small – all while laughing so hard you forget you’re learning.